My desire to share the stories of trees is directly related to the “chestnut” trees that lived in our backyard. They lined the alley behind our home that led to Holzhausen Park in Frankfurt, Germany. Holzhausen Park is where I first met the “Tree Spirit” who changed my life. I was almost seven years old and didn’t know or care about the botanical names of trees. To me they were all beautiful and unique, much like people.

My first meeting with the “Tree Spirit” along with her message: “you are here to help people understand each other better,” inspired me to see trees as living beings who cared for us.

Long before I met the Tree Spirit, this land was called Oed, meaning “desolate,” due to its location beyond the fortified walls of the Medieval city of Frankfurt.

The von Holzhausen family bought this empty plot of farmland in 1470 to create a country estate. The family name, Holzhausen means “wood-living” or “wood house.” Justinian von Holzhausen and his wife Anna Furstenberg planted a forested garden to surround their moated castle, known as Wasserschlosschen, “water castle.” It was destroyed by fire in 1552, and rebuilt in 1571 as their summer residence.

In 1729 the Holzhausen family replaced Wasserschlosschen with a new Baroque style castle, known as Holzhausenschlossen. By now the oaks, beech, elm, ash, chestnuts, willows and evergreens had grown into an enchanted forest. The Holzhausen estate became known as the “Strange Land.” It was a safe haven where philosophers, artists and revolutionary thinkers could discuss ideas regarding religion, politics and human nature.

In 1910 the last heir of the Holzhausen family gifted the estate to the city of Frankfurt, which now surrounded this once remote land. The park with its moated pond and castle were reduced in size as plots were sold to accommodate the building of stately residential homes.

A stone gate was erected on Oeder Weg, a street named for this once desolate land, to mark the original entrance of the Holzhausen estate. Two rows of chestnut trees were planted to create a pedestrian walkway that connected Oeder Weg to the castle’s moated bridge. This walkway was named Kastanien-allee or “Avenue of Chestnuts.”

Our home was located on the corner of Oeder Weg and Furstenbergerstrasse on original Holzhausen land. I lived there with my parents who adopted me in 1954. They were Americans who moved to Frankfurt in 1947 during the implementation of the Marshall Plan after WWII. Our home was a large seven-level villa that captured my imagination.

Since my parents were often busy, I was cared for by two German speaking women, named Sisi and Tanta, who lived with us. For security reasons they were forbidden to speak, read or write English. In turn, I was forbidden to learn, speak or write German. I believe this along with the many secrets surrounding my adoption compelled me to search for the deeper meaning and origin of words. Especially the names of trees and their families.

We left Frankfurt in November of 1961 when the Berlin Wall was built, and moved to the United States. We stayed in Alexandria, VA for a while before settling in Algoma, WI, a picturesque fishing village along Lake Michigan. It was all very sudden and filled with secrets.

It wasn’t until April of 2007, after the death of my adoptive and birth parents, that I finally returned to Frankfurt to reunite with Sisi and visit Holzhausen Park. My hope was to find the tree where I had met the Tree Spirit, but it was gone. As I looked around the park I could see that many of the older trees were now lying on the ground, their massive trunks were strewn throughout the park like a graveyard.

After Frankfurt, we traveled to Amsterdam and stayed on the Prinsengracht Canal, near the Anne Frank house. I had always felt a deep connection with Anne, especially since she was also born in Frankfurt. Her diary mentioned a chestnut tree the grew outside her window. Its presence was a symbol of hope and her connection to the outside world.

“Nearly every morning I go to the attic where Peter works to blow the stuffy air out of my lungs, from my favorite spot on the floor I look up at the blue sky and the bare chestnut tree, on whose branches droplets shine, and at the seagulls and other birds as they glide like silver. As long as this exists, I thought, and I may live to see it, this sunshine, the cloudless skies, while this lasts I cannot be sad.” – Anne Frank (From The Diary of a Young Girl)

During our visit I wanted to see her chestnut tree, but it was shrouded by scaffolding and nets. Apparently it was dying, which made me reflect on the fallen trees in Holzhausen Park.

When we returned from our trip I wanted to learn more about chestnut trees. The English word “chestnut” comes from the Ancient Greek word kastanon (κάστανο) meaning chestnut tree, inspired by the chestnut trees that grew in Casthanaea, Greece. Translated into Latin it became castanea, which evolved into the old English name “chesten nut” or chestnut. The Spanish call it castana.

European chestnuts, Castanea sativa, also known as “sweet chestnuts,” originated in the forested regions of the Caucasus Mountains (Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkey). The Greeks began planting chestnut trees in orchards around 2000 BCE. The Romans, beginning with Alexander the Great, planted chestnut trees along the routes of their military campaigns to create sustainable sources of timber and food. The species name sativa means “cultivated.”

The Romans planted them in Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Austria and India, where they were maintained as orchards. Based on archaeo-botanical evidence the first European chestnut trees were not planted in Britain until 1640.

My first introduction to “sweet chestnuts” was during the holidays in the United States, when I heard the opening lyrics of “The Christmas Song” written by Robert Wells and Mel Torme and sung by the Nat King Cole Trio in 1946.

“Chestnuts roasting on an open fire, Jack Frost nipping at your nose, Yuletide carols being sung by the choir, folks dressed up like Eskimos.“

What I didn’t know was that this song was a sentimental reminder of days gone by and a tribute to the American sweet chestnut tree, Castanea dentata, which was virtually extinct by 1950.

The American species name dentata, means “tooth” to describe its saw-toothed leaves.

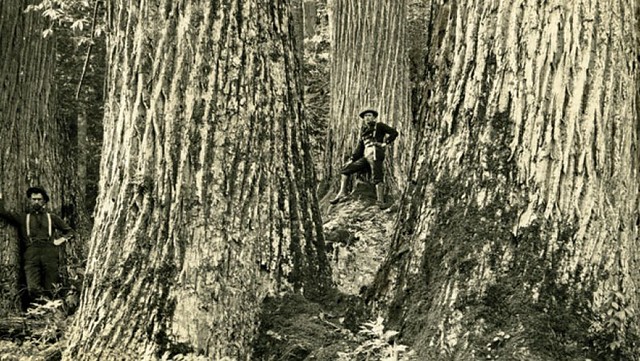

The American sweet chestnut tree had been an important keystone species that dominated the forests in the eastern half of North America. A mature tree could produce up to 6000 nuts and grow to be 100 feet tall. Some called them the “redwoods of the east”.

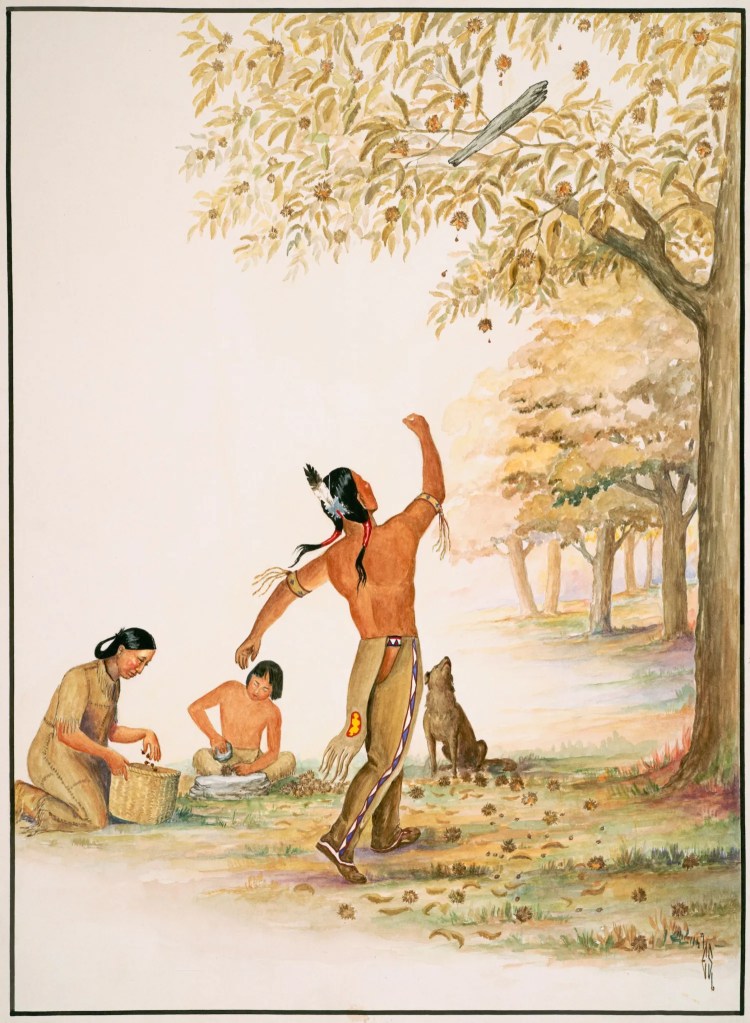

American sweet chestnuts were also an important source of food for humans, forest animals and livestock. Foraging for chestnuts was a common practice long before European settlers arrived.

To the Algonquian speaking people of Eastern North America, these sweet chestnut trees were known as Jīnquapīm (chinquapin). A name now given to several smaller species of chestnut trees and shrubs that were more resistant to chestnut blight. They continue to grow in the wild, but they produce smaller nuts than the American chestnut.

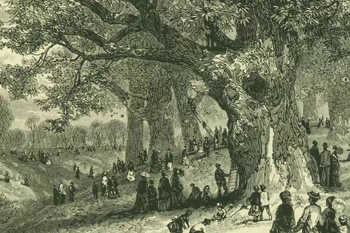

When European settlers arrived in the 1600’s and 1700’s they marveled at the size and girth of these gigantic American chestnut trees. They gathered sweet chestnuts as a food source, which could be eaten raw, boiled or roasted. They were also ground into flour and used to make bread or thicken soups and stews. The American chestnut tree was also highly valued for its wood, which was straight, strong and rot resistant. This led to logging some of these magnificent trees for their wood to build homes, barns, furniture and more.

As the demand for sweet chestnuts and chestnut wood increased, growers began to import other sweet chestnut species for commercial use such as Japanese chestnut, Castanea crenata, and Chinese chestnut, Castanea mollissima. These foreign species had built up a tolerance to chestnut blight, Cryphonectria parasitica, over thousands of years. but unfortunately they were still silent carriers. Chestnut blight killed 4 billion American chestnut trees in the United States between 1904-1949.

The subsequent loss of the American chestnut tree is considered to be the greatest tragedy in American forest history. Chestnut blight also killed significant amounts of European chestnuts throughout Europe and Asia, as well as North American chinquapin trees. But their demise did not compare to the extensive loss of the American chestnut tree, which affected 188 million acres of forestland. Some consider the American chestnut, Castanea dentata, to be functionally extinct.

The remaining ancient stumps of American chestnut can still produce sprouts, but they die from chestnut blight before they reach a few inches in diameter.

Ironically the native names, stories and recipes for American sweet chestnuts disappeared at the same time the trees disappeared. This occurred when indigenous children were being forced to give up their language, beliefs and traditions.

This all made me wonder if the tree I was looking for in Holzhausen Park was in fact a European sweet chestnut?

Today the most commonly planted chestnut tree in the United States is the blight-resistant Dunstan chestnut, a hybrid of Chinese chestnut, Castanea mollissima and American chestnut, Castanea dentata. It retains 97% of the American chestnut’s genes.

Chestnut trees belong to the Fagaceae (beech) family, which includes beech, oak and chestnut. Fagaceae, comes from the Latin word fagus, meaning “beech” tree. Fagus is based on the Ancient Greek word phagein, meaning “to eat.” Beech, oak and chestnut trees are all known for their edible nuts and valuable hardwood. Fossil records indicate that chestnut trees existed 85 million years ago in North America, Europe and Asia. Some chestnut trees can live to be 2,000 years old.

There are 9 accepted species of sweet chestnuts growing throughout the world. For more information on identifying the different species visit: The American Chestnut Foundation

- Europe and western Asia

- European chestnut – Castanea sativa (Spanish chestnut)

- North America

- American chestnuts – Castanea dentata

- Allegheny chinquapin – Castanea pumila

- Ozark chinquapin – Castanea ozarkensis

- Alabama chinquapin – Castanea alabamensis

- Eastern Asia

- Chinese chestnut – Castanea mollissima

- Chinese chinquapin – Castanea henryi

- Japanese chestnut – Castanea crenata

- Sequin chestnut – Castanea sequini

The world’s largest producer and consumer of sweet chestnuts, Castanea mollissima is China. They produce an astonishing 80% of the world’s chestnuts, which equates to 1.6 billion tons. They are followed by Spain with 180,000 tons. In contrast, the U.S. produces a mere 250-400 tons annually, while importing around 3,400 tons of European chestnuts, Castanea sativa, primarily from Italy for the holiday season.

Countries such as China, Japan and Korea have a long history with sweet chestnuts. Japanese and Chinese chestnuts are larger in size than European or American chestnuts. They boil, roast, steam, grind and puree chestnuts into a wide variety of sweet and savory dishes and beverages.

In China chestnuts are called lizi shu (Li Zi). Chestnuts are considered a culinary delicacy in Chinese cuisine as well as a popular street food.

In traditional Chinese medicine they are considered to be a warming ingredient that contains yang energy to increase vitality. This is especially important during the colder months.

- Note: Chestnuts are not to be confused with Chinese water chestnuts, Eleocharis dulcis, aquatic plants with edible corms (tubers/bulbs).

In Japan chestnuts are called kuri. Chestnuts have been cultivated in Japan since 3500 BCE.

Kuri Kinton is a one of many Japanese dishes served on New Year’s to attract good fortune. This combination of mashed sweet potato and candied chestnuts symbolizes wealth and prosperity.

In France chestnuts are called chataigne or marron. Around 1600 the French and Italians began using sugar to make Marron Glacê, or candied chestnuts.

Today candied sweet chestnuts are also a holiday tradition throughout Europe and Turkey. I have no memory of eating roasted or candied chestnuts, or eating anything with chestnuts as an ingredient. What I do remember is collecting “horse-chestnuts” as a child in Wisconsin.

I loved the feel of rolling these glossy, smooth brown nuts in my hands. I would collect them and bring them home as treasures and sort them in bowls, but I knew we weren’t supposed to eat them. I wondered if “horse-chestnuts” were related to “sweet chestnuts” and if they were actually edible?

What I learned is that horse-chestnuts are actually very toxic to horses and humans because they contain tannic acids, saponins and aesculin. Ingesting any part of a horse-chestnut tree; including the seed, bark or leaves will cause digestive problems that can affect kidney and or liver function as well as nervous disorders etc.

I returned to Holzhausen Park in 2012 and took a closer look at the “chestnut” trees behind my childhood home. To my surprise they weren’t European sweet chestnuts, Castanea sativa, they were European horse-chestnuts, Aesculus Hippocastanum! Anne Frank’s tree was also a horse-chestnut! I was confused as to why they were both called “chestnut” trees? Especially since one produced a highly desired and edible nut while the other produced toxic inedible nuts? I understood why chestnuts were often called sweet chestnuts, but why were horse-chestnuts named for horses?

In my quest to understand the source of this confusion I found a tree named the “Hundred-Horse Chestnut.” But it is not a horse-chestnut tree, instead it is the oldest and largest living European sweet chestnut tree located on the eastern slope of Mount Etna in Sicily.

The “Hundred-Horse Chestnut” received its name based on a legend that Joan of Aragon (Giovanna of Aragon), the Queen of Naples, took shelter under the tree along with 100 knights and their horses during a storm in 1486. This European sweet chestnut tree is estimated to be 2000-4000 years old. In 1780 the girth of the tree was measured to be 190 ft, but the tree has split into multiple large trunks above ground, yet share the same roots below. A small hut was built to harvest its edible sweet chestnuts to feed humans and horses alike.

Another interesting fact is that sweet chestnuts and horse-chestnuts share the same reddish-brown color, which is commonly called “chestnut.” Horses with a reddish-brown coat, mane and tail are referred to as “chestnuts.”

“Chestnuts” are also the name for harmless callous-like growths found on the inside of a horses leg.

As I began to understand how convoluted sweet chestnuts and horse-chestnuts were I decided to look into the back story of the horse-chestnut, Aesculus hippocastanum.

Horse-chestnuts belong to the Sapindaceae (soapberry) family, which includes soapberry, horse-chestnut, lychee and maple trees. Sapindaceae comes from the Latin word sapo, meaning “soap.” As a member of the soapberry family horse-chestnuts can also be a natural source of soap.

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the father of modern taxonomy is primarily responsible for this confusion because he identified and named the European horse-chestnut, Aesculus hippocastanum. The genus name Aesculus, comes from the Roman name for “edible oak acorn.” The species name hippocastanum comes from the Greek word hippos, meaning “horse” and the Latin word castanea meaning “chestnut tree.”

Linnaeus based his rationale on the physical similarities between European chestnut trees and European horse-chestnuts, since both species were large deciduous shade trees that produced similar looking “nuts.” Plus, it was commonly thought that horse-chestnuts were being fed to horses to relieve coughing, panting and digestive issues. Even though horse-chestnuts were proven to be poisonous to horses and humans, the Genus and Species names remained the same.

Another interesting connection between horses and horse-chestnut is that a horseshoe-shaped scar is revealed when a leaf drops from the twig of a horse-chestnut tree.

There are 13-19 species of Aesculus. They are commonly categorized by three regions: Europe, Asia and North America. For more information on identifying these different species visit: The Many Faces of Aesculus

- Europe

- European horse-chestnut – Aesculus hippocastanum (conkers)

- North America (buckeyes)

- Ohio buckeye – Aesculus glabra

- Yellow buckeye – Aesculus flava

- Red buckeye – Aesculus pavia

- Bottlebrush buckeye – Aesculus parviflora

- California buckeye – Aesculus californica

- Painted buckeye – Aesculus sylvatica

- Dwarf buckeye – Aesculus neglecta

- Asia

- Chinese horse-chestnut – Aesculus chinensis

- Japanese horse-chestnut – Aesculus turbinata

- Indian horse-chestnut – Aesculus indica

In Ireland and Britain, European horse-chestnuts are called “conkers.” The name conkers is based on a game where two players, each with a chestnut threaded on a string, try to “conk” each other’s “conker” until one breaks. The first recorded game was held in 1848 on the Isle of Wight.

In North America the First Nation people called the nut hetuck meaning “buck eye” because the nut resembled the eye of a male deer. Bucks represented power, protection and intuition. Deer are also immune to the toxins found in horse-chestnuts and can eat them as a food source.

Buckeye’s were collected and carried as talismans that brought blessings for themselves, their home and their family. Some would swap buckeyes as a token of friendship and connection, much like the Druids did with acorns in Europe. Some wore a necklace made with buckeyes for ceremony and rituals as well as personal adornment. It is also reported that they used to grind the nuts to release its toxins, which they scattered in streams to temporally stun fish so they could catch them with their nets.

So how do you tell a chestnut (Castanea) from a horse-chestnut (Aesculus)?

Chestnut trees can live to be 1000 years old, while a horse-chestnut’s lifespan averages around 150 years. Chestnut trees tend to have an irregular-shaped rounded crown, whereas the crown of a horse-chestnut is more erect and domed, both can grow to be 100 ft. tall.

Right: European horse chestnut, Aesculus hippocastrum with towering flower blossoms that form a domed crown.

Chestnut trees display creamy-white colored flowers that drape down in clusters of long catkins. The flowers of a horse-chestnut are erect panicles that look like towers of white, yellow, pink and red blossoms based on the species.

Right: Flowers of horse-chestnut, Aesculus hippocastanum.

The leaves of a chestnut tree are ovate and simple with individually elongated and pointed ends. The leaves of horse-chestnut trees are opposite and palmately compound with 5-7 leaflets.

Right: Plamate leaf structure – Horse chestnut, Aesculus hippocastanum.

The outer shell of a chestnut bur is yellow-green with a long bristly capule containing 1-4 nutlike seeds or chestnuts. The bur of a horse-chestnut is also yellow-green but with a shorter spiky capule (some species are smooth) typically containing only 1 nutlike seed called a conker, buckeye or horse-chestnut.

Right: Horse-chestnut burrs are thicker with shorter wider spaced spikes containing one nut.

Sweet chestnuts are triangularly shaped, they have a flattened side with a pointed end and tuft or tassel, also referred to as a “flame.” Horse-chestnuts are irregularly shaped and rounder without a pointed end or tuft.

Right: Horse-chestnuts are irregularly shaped and rounder.

It’s clear to me now that there is quite a difference between sweet chestnuts and horse-chestnuts and how easy their differences can be overlooked. What I have learned during this process is how important it is to understand the stories of trees and how they were named. Names carry important clues, which are sometimes hidden due to translation, misunderstanding or lost stories. In the case of the “chestnut” it’s literally a matter of life and death that we know the difference between these two ancient trees and their “nuts.”

When we lose our understanding of trees and their stories we lose a part of our connection to nature itself. We also have to accept that we live in a dynamic world where words and names are being continually changed, discarded and reinvented.

As I was working on this very story I discovered that the original “Avenue of Chestnuts” Kastanien-Allee was recently renamed “Alley of Emil Mangelsdorff” Emil-Mangelsdorff-Allee, on April 11, 2025.

Emil-Mangelsdorff (b. 4/11/1925 – d. 1/20/2022) was a famous Frankfurt jazz musician who helped give birth to the Swing Youth era during Nazi Germany. He was imprisoned by the Gestapo and forced to serve in the German Army, only to end up becoming a Russian prisoner of war. After his release in 1949, he became a professional jazz musician. His last concert was held at Holzhausenschlosschen “Holzhausen Castle” on November 1, 2021. The name was changed in honor of his 100th birthday.

What’s fascinating to me now is that my birth mother Karin, who I reunited with in 1994 described herself as a “swing kid.” She was born in 1933 and lived through the bombing of Frankfurt during WWII. She and her friends were self-described “beatniks” who opposed the Nazi regime, they listened to jazz in coffee clubs during and after the war. Before she passed away in 1995 she asked me to write the truth of how I was separated from her and how we found each other. She also loved trees and believed in spirits. I can easily imagine her listening to Emil-Mangelsdorff’s music in one of those clubs. She believed that she was sending her spirit to me every day of my life and that I was receiving it. It’s possible that the Avenue of Chestnuts did lead me to her and this story.

I will never know for sure what tree the “Tree Spirit” appeared in, what I do know is that we should never stop wondering.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this journey down chestnut lane… and that you continue to explore the countless stories waiting to be discovered and understood.

If you would like to know more about my personal story and the Tree Spirit, you may be interested in my autobiography: The Guardian Tree – the true story of Carmen Sylvia.

“It is not so much for its beauty that the forest makes a claim upon our hearts, as for that subtle something, that quality of air that emanation from old trees, that so wonderfully changes and renews a weary spirit.” – Robert Louis Stevenson